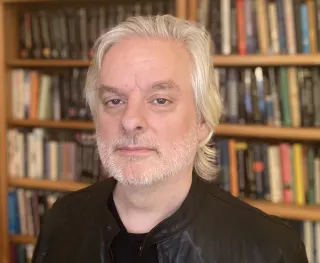

A luminary in contemporary philosophy, David Chalmers has a unique perspective on the rise of large language models and other generative AI programs. We spoke with him ahead of his upcoming speaking engagement at Washington University.

On September 20, as part of the TRIADS Speaker Series, philosopher David Chalmers will visit WashU to pose a seemingly straightforward question: "Can ChatGPT Think?"

While Chalmers isn't in the business of providing a direct "yes" or "no" answer to philosophical quandaries like

these, he's perhaps one of the best-qualified minds to ask the question and unravel its potential implications. Whether in the form of books or TED Talks, Chalmers has grappled with the nature of human consciousness for the better part of three decades. And on a parallel track, he has kept a close eye on the development of artificial intelligence, penning journal articles on the subject and presenting at AI conferences since the early '90s.

Chalmers, now a New York University Professor of Philosophy and Director of the NYU Center for Mind, Brain, and Consciousness, met via Zoom to discuss the marvels and mysteries of ChatGPT, how he uses philosophical questions to gauge the progress of large language models, and his two years spent at Washington University as a postdoctoral fellow.

RSVP here to attend Chalmers' talk.

Tell us about your own experiences with ChatGPT. What do you use it for, and what impact has it had on your life as a professor and as a philosopher?

It's had many different kinds of impact. Theoretically, I think it's just really interesting to think about, because I'm interested in AI and the possibility that we might one day have AI systems that are actually conscious, actually thinking on par with human beings. These systems are the first things we've seen where it starts to be a serious question to at least compare them to human-level intelligence. And although they still fall short in many ways, with all kinds of glitches and mistakes and things they can't do, it's really quite remarkable what they can do. So as a philosopher, that's just interesting to think about.

Practically, it impacts my life in many ways. As a professor, I have to worry about whether students might be using ChatGPT for their papers and whether that's a good thing or a bad thing. But if I'm doing research, every now and then I'll try an idea on ChatGPT and it will occasionally have interesting things to say. Just like a smart student can be a good sounding board, a smart AI system can also be a good sounding board.

Have you had a moment with ChatGPT or another generative AI program that forced you to pause and consider the intelligence of what you were interacting with, or have the seams always been visible for you when interfacing with these systems?

So far, I'd say there are seams, but it's increasingly impressive what they can do.

I have a few favorite philosophical questions that I like to ask these systems and they've gradually been getting better over time at responding. One of them is an old classic: the difference between a difference in degree and a difference in kind, is that a difference in degree or a difference in kind? That's a pretty complicated philosophical question.

When I asked ChatGPT-3 that back about four years ago, its response wasn't bad, but it wasn't great. Now, the latest version of ChatGPT or Claude actually gives a pretty impressive answer to this question, much better than many professional philosophers might get. My only qualm is I'm not sure if it might've been trained on my previous interactions with it. So maybe it's got a kind of a jumpstart on this question; if you ask it too many times over the years, you become part of the training data potentially.

This has to be a very exciting time to be in philosophy because the question of machines approximating human behavior has been a speculative idea for centuries. But it's no longer a question of, "if we built a machine that could do this..." Instead, we're now regularly interacting with programs like this. Has the ground shifted in philosophy now that these tools are in wide use?

I actually did my PhD, which is now 30-odd years ago, in an AI lab. And people used to say around then, "A year spent working in artificial intelligence is enough to make you believe in God."

But the AI systems we had at that time were so primitive, and that continued, really, up until about 10 years ago. And sometime around then there was an explosion where you got AI systems that were good at certain specific things, like very good at image recognition, very good at language translation, very good at playing Go.

The new thing in the last five years is these language models, like the GPT systems, which are suddenly good at so many things, their general intelligence was previously a science fiction scenario.

Suddenly, some of these scenarios are becoming a reality, like having an AI system that passes the Turing test, behaving in a way indistinguishable from a human. Previously that was unthinkable. Now suddenly it's thinkable, maybe even happening.

Of course, we have to ask about your time at Washington University.

It was my first job after I got my PhD. I was a postdoc for two years, from '93 to '95. It was a McDonnell fellowship from the James S. McDonnell Foundation in the philosophy-neuroscience-psychology program, which was just starting up then. We had a great group of people there. It was a very exciting time at WashU. I published my first book on consciousness around that time after giving it a good going-over with the WashU grad students. Andy Clark and I did work on the extended mind that has gone on to have a big impact. That all came out of this philosophy-neuroscience-psychology program at WashU, and that was just the first two years. Now here we are 30 years later, and the PNP program is now an institution. It's possibly the leading program that integrates philosophy and neuroscience and psychology in the world. So I'm proud to have been there at the beginning. I've not been back to WashU since I left in '95, so I'm really looking forward to being there.